Album Review: “The Man Who Sold the World” by David Bowie

With the 50th anniversary of a classic David Bowie album upon us, it seems like the perfect time for a listen.

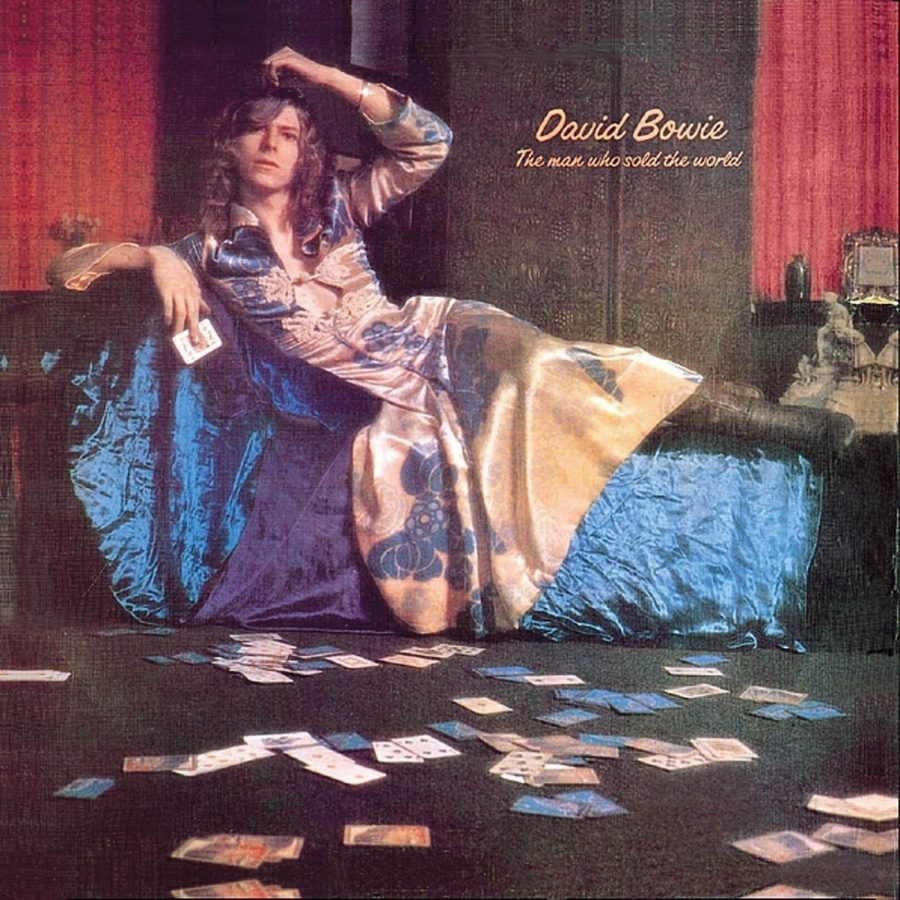

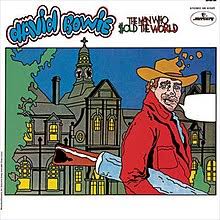

The best-recognized version of the cover, featuring Bowie in his Haddon Hall apartment in a Michael Fish dress, was only ever used on the original UK release. Vetoed by executives for the American release, it wouldn’t be reinstated until 1990.

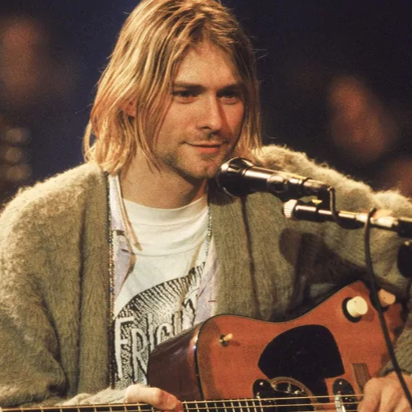

DAVID BOWIE sits in the pantheon of late, great rock-and-roll artists, with a music career that spanned almost 50 years. You probably know at least some Bowie, be it “Life on Mars”, “Space Oddity”, Ziggy Stardust, “Heroes”, or even “Under Pressure” with Queen. However, there’s a strong chance that even the unfamiliar would recognize the song “The Man Who Sold the World”. But there’s one complication with that – the performance of “The Man Who Sold the World” most people hear is by Nirvana, with iconic vocals by Kurt Cobain. Many don’t even know the famous MTV Unplugged recording is a cover of a David Bowie song released in 1970.

November 4th, 2020 marks the 50th anniversary of the album The Man Who Sold the World’s American debut. Consequently, with such a landmark date approaching, I felt the album and its role in Bowie’s career merited a revisit. His third album, it came before he was known for anything other than “Space Oddity”. Unfortunately, this album would not be his breakout album – upon release, it was not especially a commercial or critical success, even in more receptive Britain.

However, it had a lot going for it – namely a strong lineup. While Bowie controlled the vocals, he collaborated with guitarist Mick Ronson and drummer Mick Woodmansey for the first time. It was his second album with producer Tony Visconti. Also attributed were Ralph Mace on the Moog synthesizer and ex-Abbey Road engineer Ken Scott. The result of this collaboration was an album whose greatest strength and weakness is in its diversity. It ranges sonically from metal to blues-y to whimsical, and thematically from dystopian to Gothic to sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Through it all is a pervasive darkness accomplished through a heavy, unsettling sound, which under Visconti’s oversight bound the disparate tracks into a coherent album.

It opens with “Width of a Circle”: a near-monolithic start to the album, coming in at just over 8 minutes long. Between Bowie’s strained vocals, Mick Ronson’s guitar, and Mick Woodmansey’s drums, there is a Ziggy-esque sound – however, Visconti’s bass distinguishes it. It sets the tone for the album, with its lyrics centered on an abstracted encounter, and a hard rock sound. In a move that would prove typical for Bowie, it is divided into two parts, the latter distinguished by a more pared-down sound.

Next is “All the Madmen”, a wonderfully tongue-in-cheek look at society. Its narrator prefers being in a mental asylum, (maybe) pretending to be insane, to the cold outside world – he’d rather be there with “all the madmen” than all “the sad men roaming free”. The only sane people are locked up with him. The intermittent verses of spoken word and nonsense lyrics, and Mace’s Moog synthesizer lend a darkly humorous song a suitably disconcerting sound.

“Black Country Rock” is a different story, and one that merits some explaining. Ironically, for an artist striving for a commercial breakthrough, Bowie was very aloof for much of the recording process and this period of his career. His absences during recording and excessive time spent away with wife Angie created friction with the band and led to a lot of haphazard recording just before the deadline for the album.

The jam session approach the band took to writing, by choice and necessity, shows the quality and strength of the instrumentals on the album. But Bowie only came into the studio to okay the jams and lay down vocals at the tail end of production; while it largely doesn’t show that most of the lyrics were hastily written, tracks like “Black Country Rock” lack the narratives imbued in the others, and the listener can tell the lyrics were not the focus. It remains a good rock song, and Marc Bolan of T. Rex’s influence is clear.

Following the uncanny “After All” is “Running Gun Blues”, a personal highlight of the album. It’s a grim and haunting contribution to the anti-Vietnam genre emerging from the United States. Following the lyrics only makes it more visceral, and its title likely refers to PTSD. Ronson’s work on guitar and Woodmansey’s drumming make it a solid rock track, but the eerie vocals and use of the stylophone carry through the unnerving undertones on the rest of the album.

“Saviour Machine” provides a very different narrative, playing off a dystopian concept. Its titular narrator is a computer devised to solve all the world’s problems; once successful, it realizes humanity is doomed without shared adversity, which culminates in it going insane. It is inadvertently a song about A.I., from a time before the concept was even widespread. The use of the Moog perfectly suits the theme of a technological dystopia.

The final track, “The Supermen”, has a looming, ominous sound that latches onto the imagination. Referencing a Nietzschean concept, the Übermensch, it conjures up images of the supernatural and Lovecraftian occult. The haunting background vocals and chanting give it a spacious sound even as Bowie bears down on the listener.

Last here but not least, I have to address the title track. Following “She Shook Me Cold” – the nearest song to metal on the album – “The Man Who Sold the World” is almost jarringly restrained. Despite this, it’s a juggernaut on the album, and not just because of Nirvana. Its lyrics are enigmatic, the vocals are haunting, and its sound – defined by Ronson’s iconic looping riff, subtle organ, and the unmistakable guiro – is incredibly complex. According to Bowie, the song was written about searching for and coming to terms with oneself; it makes sense, given his use of various personas over the course of his career. It’s no wonder that Kurt Cobain singled it out.

It’s said that a good cover changes the context of a song in a meaningful way. Cobain’s cover of the song immortalized it. However, the greatest change in that cover’s context came after his death four months later – Nirvana’s famous performance on MTV Unplugged was one of Cobain’s final creative outputs. It seems fitting that such an inscrutable song has become linked to such a reserved icon.

While this album may not be as well-recognized as some of Bowie’s other works, it is integral to his career as a whole. It was the beginning of his “classic period”, over a decade of commercial success and quality music. He incorporated theatrics, leaning into his androgynous side with the famous “man dress” on the cover. Most importantly, he embraced collaboration: Ronson and Woodmansey would return on Ziggy Stardust as members of the Spiders from Mars. He would work with John Lennon, Nile Rodgers, and Brian Eno, and publicized Luther Vandross and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Even in terms of content, many themes and undertones from The Man Who Sold the World would reemerge on seminal works – dystopias, mental illness, Nietzschean philosophy, and the occult, especially, made it onto Ziggy and Station to Station.

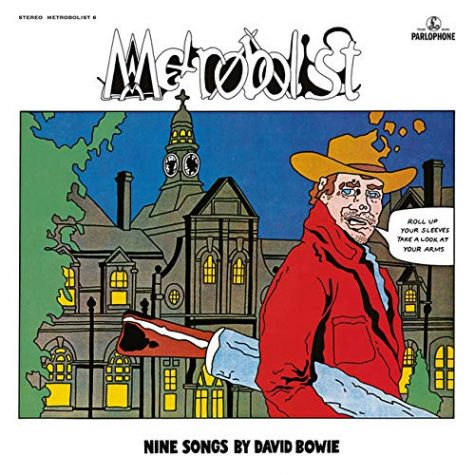

For all those reasons and more, this is an album still worth listening to, especially for the Bowie fan. It’s not the most approachable, and it might take a few plays to get your head around. Don’t discount everything other than the title track for that –once you start picking up on the subtleties, there’s a lot to appreciate. It benefits from an attentive listen, and following the lyrics helps. Of course, all this holds true for any album. But if you do want to try it, I would even suggest waiting until November 6th, when a fiftieth anniversary remix by Visconti will be released. It will be entitled Metrobolist, Bowie’s original name for the album, which was changed at the last minute. Even after listening to this album countless times, I’m still excited to give it a listen.