Book review: Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

This highly accessible and imaginative novel offers a look at a technology-dependent future with surprising breadth, but at times lacks depth.

April 12, 2021

It’s not often that a novel can be described as “unknowingly prescient”, but if that label suits any book, it would be noted author Kazuo Ishiguro’s latest. Klara and the Sun walks the fine line between offering pandemic escapism and unwelcome realism. Ishiguro is known for a preoccupation with themes like loneliness an d employing narrators that speak from the background, and Klara is no exception in his catalogue – making it unexpectedly relevant.

d employing narrators that speak from the background, and Klara is no exception in his catalogue – making it unexpectedly relevant.

Most notably, Ishiguro excels at bringing in a distinct perspective from a truly unique narrator. The story is told through the eyes of Klara, an AF, or Artificial Friend. Klara is an android, a humanoid robot, intended for one purpose: to prevent a child from growing lonely. While nonhuman narrators are not so exceptional in fiction anymore, it is Klara’s outside perspective that truly sets apart the telling of this otherwise rather conventional (but thematically spot-on) story.

Ishiguro balances Klara’s novelty carefully. Her exceptional astuteness runs up against her not-quite-understanding of human emotions and irrationality. However, her grasping to make sense leads to unexpectedly poetic interpretations of humanity. For example, describing the sound of crying as, “her voice loud… as if it had been folded over onto itself, so that two versions of her were being sounded together, pitched fractionally apart.”

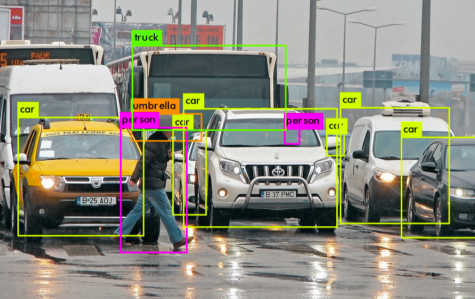

He only alludes to how fundamentally different from us she is in her times of stress, where her vision seems to disintegrate into “boxes”; think object detection software like Tesla’s “Autopilot” and modern surveillance equipment.

Predominantly, however, Klara still seems to blur the lines of humanity and authenticity. She handily demonstrates the attributes we self-congratulatorily assign ourselves: curiosity, capacity for learning, empathy, and even hopefulness. Yet her existence attests to a society less of technological wonders, but more of horrors. Technology, recklessly embraced, made for a future where society is so dysfunctional that it had nowhere to turn but to more technology. What’s most striking about this premise is that aspects are no longer as implausible as they might have seemed just last March. Its prescience has been realized right on cue, and Ishiguro’s damning look at human exceptionalism seems less damning today, with the pandemic bringing such pessimism into sharp relief.

In Klara, humans have created a miserable and direly antisocial future. There are robots who can perform almost as well as we can. Yet little has fundamentally changed or improved. Pollution, as manifested by a “Cootings Machine” (Klara’s label for a piece of heavy machinery), remains, despite the prevalence of such unbelievably advanced technology. What seemed so unimaginable – children learning remotely and virtually so that they have just about no social skills, with unhealthy amounts of pressure placed on them, then further divided by inequitable access to education – is proving dangerously close to reality, rather suddenly. The children are doomed to inherit this society, and the adults realize it with resignation. The question Ishiguro poses is, “How can we possibly maintain our identities in a society that presses us, or forces us, to conform, or be left behind and ostracized?”

Ishiguro had begun writing the novel before he won his Nobel Prize in 2017. What must have seemed so novel until last year – then classifiable as science fiction – now ring with fact. Even a pandemic itself was novel, yet here we are, just past the anniversary of it’s arrival.

I’ll admit that I think my own perspective – that of a young adult in unprecedented times – has also affected by perception somewhat. Distance learning immediately jumped to mind upon seeing Josie, Klara’s teenaged charge, taking online classes; however, online learning here provides the way for such privileged students to access the most sought-after instructors. But Ishiguro realizes the consequences of this self-imposed isolation to an extreme, depicting the strained “interacting meetings” that parents convene to force their children to interact and pick up social skills. This inadequate substitute for genuine socialization is eerily reminiscent of our worst fears about the pandemic.

I don’t think that this book does everything right. Klara’s voice works against the writing at times, dulling the impacts of the plot, though it also works the sharpen the rawest moments. Reading other reviews suggests that I’m not alone in having mixed feelings; there seems to be a mixture of adoration and confusion. They’re split between this being Ishiguro’s latest masterpiece, or an exception to his prodigious career. I don’t know enough about his other work to say where I fall, though I think it has certainly biased the reception; it seems telling that his name appears larger than the title on the first edition cover.

But as someone fairly removed from the literary world of booklists and bestsellers, I still think it has proved itself worth reading, even if you’ve never heard of Sir Kazuo Ishiguro or his other acclaimed works. I don’t think it’s all that those diehard fans make it out to be – it didn’t strike me as a life-changer or tearjerker, but it certainly struck a chord. The themes are varied, looking broadly at what it means to be human, as immediately juxtaposed by Klara. It also touches on loneliness, the ways people care for one another, their motivations, and the strange tolls that strange circumstances can take on one. It addresses other very topical issues, but in a veiled way, not really exploring their ramifications. The book depicts artificial intelligence, consumerism and obsolescence, and genetic editing (the topic Ishiguro has said strikes him as most pressing), but only in the background, leaving the interpretation open to the reader for better and for worse.

a chord. The themes are varied, looking broadly at what it means to be human, as immediately juxtaposed by Klara. It also touches on loneliness, the ways people care for one another, their motivations, and the strange tolls that strange circumstances can take on one. It addresses other very topical issues, but in a veiled way, not really exploring their ramifications. The book depicts artificial intelligence, consumerism and obsolescence, and genetic editing (the topic Ishiguro has said strikes him as most pressing), but only in the background, leaving the interpretation open to the reader for better and for worse.

In a word, Klara and the Sun is muted. It is largely melancholic, with moments of joy. It leaves both something to be desired and something fulfilled. There is an abundance of unanswered questions, but it may be for the better that the answers are left open-ended for our consideration. Most importantly, it imparts something like hope: even as things are bad in Ishiguro’s unwelcome future, they get better. Life goes on. Hopefully, the same can be said for us.

Larry • Dec 19, 2021 at 8:43 am

Stumbled on your review. Excellent, well written, better than many, from well-known review sites. Thank you

Leonie • Jul 24, 2021 at 11:52 am

I really like your review and your take on things so I wonder if you have maybe a theory what the Sun represents.. I wonder if it is a personification of something, maybe God (especially since Klara addresses it with the pronouns he/him) or if she is just so wired to the idea that the Sun is some sort of greater help simply because SHE can only function with its embrace. And maybe also the Barn: should it represent something, maybe heaven or a palace? What do you think?

Anonymous • Apr 26, 2021 at 9:15 pm

What does RPO mean?

Ryan Keating • Apr 29, 2021 at 10:04 am

If you’re referring to the RPO building in the novel, I’m not sure. I think it’s just an a made-up acronym for some corporation.